"The National Foodball League" Project: Cleveland

by Mike Lunsford, GGR Editor-In-Chief

There was never a time as I was writing these food history/regional history/sports history mash-up articles that I thought to myself “these could be a good distraction for people traumatized by an attempted coup of our government.” But here we are. If 2020 has taught me anything, it’s that when you think things have gotten as bad as they can get, they can ALWAYS get worse. This leads me to a perfect tie-in for a city whose sports teams have spent the last 70 years in various stages of “things can always get worse:” Cleveland. But Cleveland is so much more than that. It is a city that grew because of some amazing principles. It has a diverse population because of a progressive mindset, and has a rich and unique history.

History

Ohio was an important location for millennia and many indigenous communities called the area home. With it’s moderate climate, access to rivers, and dense forests, the area was attractive to many people. In the late 17th Century, the French were the first Euorpean settlers to enter the region, and the first to make records about the indigenous people living in Ohio. They documented six major groups: the Shawnee, the Seneca-Cayuga, the Lenape, the Wyandot, the Ottawa, and the Myaamia. As the 13 original colonies expanded after the Revolutionary War, the colonists treated these nations no better than any of the previous states we’ve discussed. It was more broken treaties, brutal attacks, and forced relocation all in the name of white settlers. It sucks that this was the standard in almost every example of westward expansion, especially for Ohio because it was home to some of the most prestigious indigenous leaders such as Tecumseh and Blue Jacket.

The city of Cleaveland (not a typo) was founded in 1796 and became an important supply post for the U.S. during the War of 1812. With it's proximity to Lake Erie, (and later, the connection to the Mississippi River and Atlantic Ocean because of the Ohio Canal and the Erie Canal respectively) the city grew by leaps and bounds. Much like its predecessor in the Foodball League articles Buffalo, Cleveland grew and benefited greatly because of the canal systems. The area was a vital connecting point between the East Coast and the Midwest.

Wanna know why the name of the city changed? It’s so dumb: they couldn’t fit the whole name on the masthead of the newspaper. The printer dropped the first “a” and the city was like “Know what? Fuck it. It looks better that way.” And that’s how Cleveland got its name.

Anywho, let’s get back to the history, because this city did some really dope stuff. Cleveland was home to many abolitionists. It was nicknamed “Station Hope” because it was a vital stop on the Underground Railroad, along its Lake Erie neighbor Buffalo. This desire for racial equality, and the area’s progressive ideals regarding immigration allowed the city to grow exponentially after the Civil War. By 1920, it was the 5th most populated city in the country, with 30% of that population being foreign-born. And that inviting attitude mean a large influx of African Americans moved to the area, as the South continued to show its ass even after the Civil War.

Cleveland continued to be a place of innovation and excellence. Their sports teams saw great success as the baseball team won a few World Series, the Browns were a dominant football team continually from the 40s through the 60s, and it was the place where the term “rock and roll” was coined by radio DJ Alan Freed.

The Cleveland renaissance

The Browns continued to have success in the new NFL into the 60s, but the city fell on some hard times. Economic growth slowed, and racial tensions rose because of institutions such as red-lining and housing discrimination (ya know, like the kind of shit Donald Trump did!). In one of Cleveland’s darkest moments, the river which runs through the city caught fire (again) in 1969. The Cuyahoga River was a mess because of all the dangerous chemicals dumped into it. In fact, the “River on Fire” name has been applied to many products and euphemisms for the city.

However, these dark days of racial bias and industrial pollution became important catalysts for change. The environmental movement kicked off, and it brought attention to the dangerous industrial pollution. The Cuyahoga reclamation project was one of the first of its kind to help clean up the damage done by companies dumping toxic chemicals into waterways. And the first African American mayor in the United States? That’s right: Cleveland’s own Carl B. Stokes. Mayor Stokes was instrumental in restoring the Cuyahoga.

The city has overcome some rough times and has been recovering well. Their legacy of inclusivity and diversity has caused the city to flourish. In fact, after a horrible stretch of heartbreaking sports losses: The Browns lost in the AFC title game three times in the 80s and 90s, and the baseball club lost the World Series in game seven twice. Homegrown NBA superstar Lebron James got the Cavs to the championship four times, but lost every single time. The city finally saw the promised land again when, in 2016, Lebron led the Cavaliers to a stunning NBA Finals victory over the heavily favored Golden State Warriors. Even more impressive? The Warriors had been up 3-1 in the series as Lebron and the Cavs stormed back to win three in a row. It was Cleveland’s first championship since 1964.

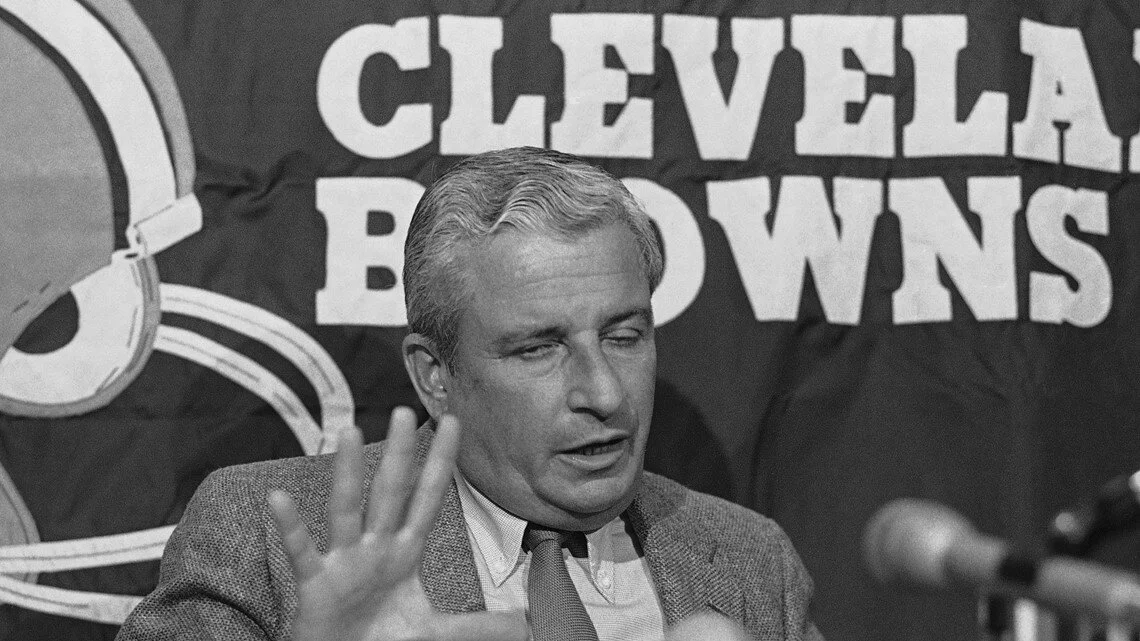

Now, since I create football logos mashed-up with local iconic foods, I want to spend a little time on the football team, in particular the sack of shit known as Art Modell.

F**KING ART MODELL, MAN

Remember how Robert Irsay fucked Baltimore as hard as he could when he stole the Colts from Baltimore in the middle of the night? I wrote a whole article about it if you didn’t know. While Modell was a scumbag, he wasn’t able to top Irsay’s douche-baggery. He came close, though.

Just like the Colts, the Browns were one of the most successful franchises in the 50s and 60s when the NFL was quickly gaining popularity. Art Modell took ownership of the storied Browns franchise in 1961. They won a couple of championships and things seemed great. However, Modell was a shitty owner in the sense that he made bad business decision after bad business decision. In 1975, he made a deal with the city of Cleveland that meant he paid the rent for Cleveland Stadium for the next 25 years but did not share the revenues of suite sales with the other Stadium tenant, the baseball team. (Yes, I know their name but I’m not fucking saying it. Thank God they’re finally changing it.) The baseball team’s suite sales were making way more money than the Browns, and they were rightfully upset. 81 home games for baseball vs only 8 for football is not difficult math. The baseball club worked with the city to build a new stadium where they could get the revenue from suite costs, and joined forces with the Cleveland Cavaliers on what was called the Gateway Project. The project built a new baseball stadium and basketball area for the Cavs, but Modell was not interested and stayed where he was at. He never once thought that the baseball team’s departure would hurt his revenue.

Due to Modell’s shortsightedness, the Browns hit hard financial times immediately. Now mind you, the baseball club left in 1994 for their new home, Jacobs Field. By 1995, Modell made his infamous decision to leave. How could one year’s revenue screw the Browns up so quickly? Well…Modell always sucked as a business man. He had long been one of the poorest owners in the NFL. He'd borrowed the bulk of the money he'd used to buy the Browns in 1961, and had spent most of the next 34 years in financial difficulty. He even dumped some of that debt onto the team. In 1994, Modell was desperate to replace those lost suite fees. He requested an issue be placed on the ballot to provide $175 million in tax dollars to refurbish Cleveland Stadium, even though it wouldn’t come up for a vote until September of 1995. Modell was impatient.

Modell told his board of directors he didn’t think the tax referendum would pass. He started talking to other cities…specifically, Baltimore. Now, Baltimore had been in talks with the NFL and they were promised an expansion team, but that didn’t stop Modell sending Browns minority owner Al Lerner to speak to Maryland’s new Stadium Authority chairman, John Moag. Moag was licking his chops. He already had a contract drawn up and ready to go as he tried to convince the Cincinnati Bengals to move to Baltimore. In fact, the contract Moag gave Lerner still had the word Cincinnati in it several times! Lerner brought it back to Modell, and told him he should sign it. Ultimately Modell did sign it. He felt he had no choice as he believed the Cleveland voters would not pass the tax referendum. In the end, his impatience was the reason he signed and chose to move the franchise to Baltimore. But wait…there’s more.

On November 6th, 1995, Art Modell held a press conference to announce the move of the Cleveland Browns. You know where he held the press conference? Camden Yards, in BALTIMORE. His justification was that the city did not have the funds or the political will to refurbish Cleveland Stadium or build a new place for the Browns to play. What happened with the vote held to determine the tax referendum? On November 7th, 1995, it passed almost unanimously. Regardless of the result, Modell refused to reverse his decision, saying this:

The bridge is down, burned, disappeared

“My mind doesn’t change with the rising and setting of a few suns.” -Art Modell…or maybe JRR Tolkien.

This man had publicly chastised Robert Irsay for moving the Colts to Indianapolis. He had testified in court in favor of the NFL when they sued Al Davis for moving the Raiders to Los Angeles. AND he had promised to never move the Browns. In the end, this man not only moved his team, but did so even after Cleveland found the “funds and the political will.” He was impatient, and did not even give his team’s home city the opportunity to counter Baltimore’s offer. He committed the same business practices for which he scolded Irsay.

The Browns finished the 1995 season in Cleveland and left for Baltimore at its conclusion. However the only things that went with them were the players, coaches, and contracts. The NFL stepped in and refused to allow the same sort of outright thievery the Colts committed 12 years prior. The Browns moving to Baltimore would be treated like an expansion team: new team name, new colors, new records, etc. All of the Cleveland Browns history and identity would remain in Cleveland until there was a new owner lined up for the the Browns and a new stadium built. The Browns would essentially be in suspended animation until 1999, when they were reactivated.

“Do you wanna play the Bengals? It doesn’t have to be the Bengals. Okay…bye” Yes, I made the same frozen joke in 2 articles. You’re welcome.

It sucked to lose the Browns, but ultimately, it was only 3 years without a team and they got to keep their colors, history and name. So, the people of Cleveland didn’t hold any ill will towards ol’ Art Modell, right?

Seen at the West Side Market. Honestly? I love it. Fuck Art Modell.

He never set foot in Cleveland again. Supposedly, he was an “emotional wreck” after signing the deal with Baltimore, but guaranteed no one felt bad for him ever. It’s like feeling bad for someone who cheated on their spouse while they’re in therapy together, and says "but babe, I felt bad about it!” That’s some abuser shit right there.

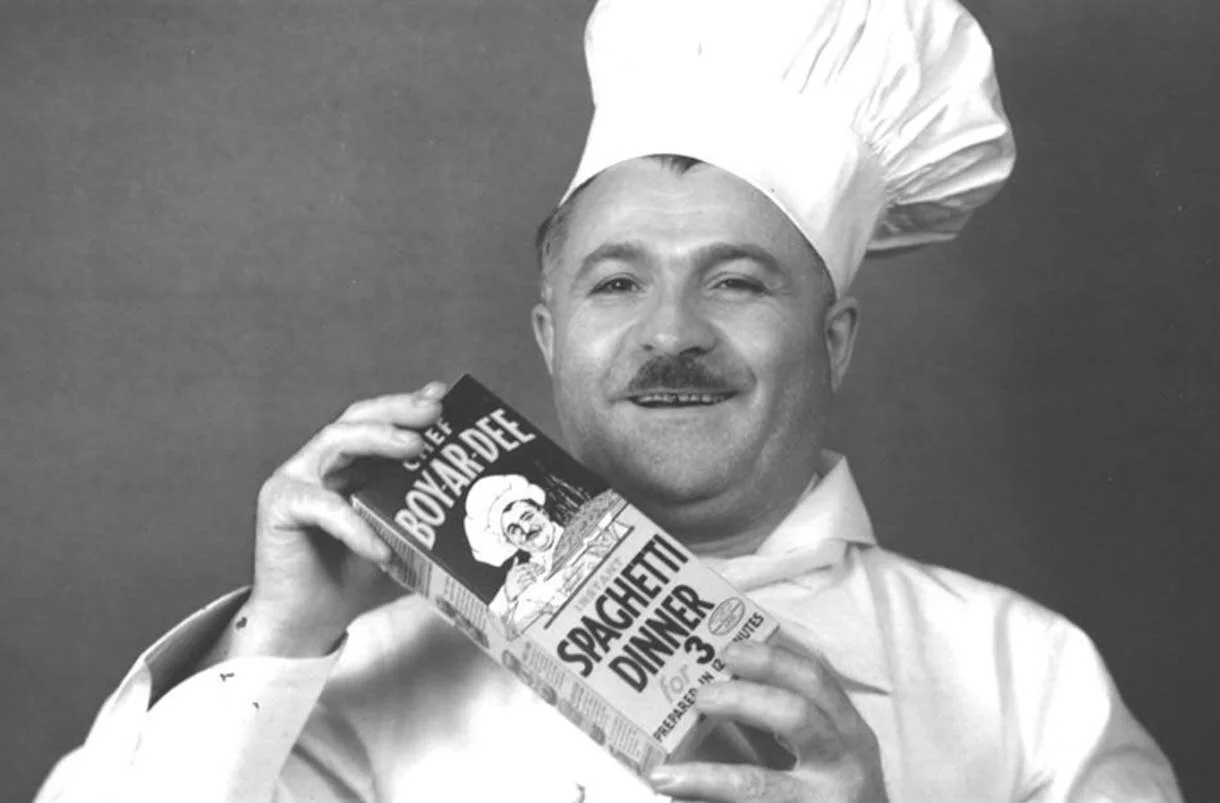

Food

As previously mentioned, Cleveland is a city full of diversity due to the influx of immigrants. In fact, one of their favorite sons is internationally known. His name is Ettore Boiardi, but you know him as Chef Boyardee. Now, most people hear that name and roll their eyes. “Eww, that processed, cheap pasta in a can? Barf.” That’s not an unexpected response at all, but bear in mind: that cheap pasta in a can has fed millions for decades, and is an affordable way for many people to feed their families. Is it gourmet? HELL NO, but that was actually Boiardi’s intent. He came from Italy in 1914, and worked his way up to head chef of the Plaza Hotel in New York City. THE PLAZA! CHEF BOYARDEE WAS THE HEAD CHEF OF THE PLAZA! Instead of just being a famous chef who let his fame garner him accolades, he started his own restaurant in Cleveland called Il Giardino d'Italia (The Italian Garden). He started selling his famous pasta sauce in cleaned out milk bottles. When the depression hit, he created bundles including that famous sauce, dried pasta noodles and parmesan cheese to help feed struggling families. He turned that in to an empire with his anglicized “Chef Boy-Ar-Dee” line. It became a food provider for Allied forces during World War II and the leading canned food brand in the US. So yeah, his products may be “low class,” but the dude gave a crap about others and received a Gold Star of excellence from the U.S. government for his service. Let that sink in for a moment before you trash beef-aroni.

The Cleveland Boy-Ar-Dees? Might’ve been cool, but I’m not getting sued. lol

The theme of this food article could be boiled down to one subject: the impact of immigrants. In particular, Eastern European immigrants had a massive impact on the culinary identity of Cleveland. That is reflected in the choices (yes, plural) I made for the Cleveland Foodball team logos.

Local mainstays of Cleveland's cuisine include an abundance of Polish and Central European contributions, such as kielbasa, stuffed cabbage and… the first logo for the Cleveland Foodball team: pierogies. A symbol of Polish and Eastern European food, the pierogie is a type of dumpling made with unleavened dough. It can have a variety of fillings: potato, meat, mushrooms, sauerkraut, and even fruit. The most famous (and most delicious in my book) is the potato pierogie.

AND IT’S TOPPED WITH FRIED ONIONS????? MOTHER OF GOD!

Since I want to highlight the culinary contributions of the Eastern European population to the diet of Clevelanders, we must look at a sandwich that was born there. Much like Tampa’s version of the Cubano (*ahem, the CORRECT Cubano), their famed Polish Boy is a mash-up of the many cultures that interact with each other in the city. The sandwich consists of a polish sausage, grilled or deep-fried, and covered in french fries, cole slaw, barbecue sauce, and/or hot sauce. And it’s all fit, inexplicably, onto a bun. Because, why not, right?

Not pictured: the clean t-shirt you will need in order to replace the one you ruin while eating this.

You food snobs out there might say, “But that’s too many things on a sandwich at the same time!” Let me state that Michael Symon, Iron Chef winner and James Beard Award recipient, says this is the best sandwich he’s ever had. There’s no way this isn’t delicious, and I might have to find a way to get one of these bad boys.

So, I present to you, the dual-wielding power of the Cleveland Foodball Team: a franchise deserving of 2 logos since Art Modell tried to steal you and take you to Baltimore. I present: the Cleveland Pierogies and the Cleveland Polish Boys

Those two logos would make for an awesome meal. Combined, I would call it “the Cleveland Special.” You may need a nap and a trip on the treadmill afterward, but it would be worth it for sure. And to commemorate your love of the designs or Cleveland itself, you can get your own t-shirt/long sleeve/hoodie by clicking here for the Pierogies logo and here for the Polish Boys.

Cleveland was a fun city to research. It has a rich history and it’s surprising to me that it catches so much crap from others (mostly Pittsburgh residents). Sure, their sports teams had a rough stretch for 50 years. Sure their river caught on fire (twice), but this is city is a symbol of America! Sure, there have been missteps, sure there have been awful, disgusting decisions made. But in the end, its strength comes from leaning in to its diverse population and accepting that we’re better together than apart. Just like the Polish Boy, would all of those things be tasty on a plate, separately served? Yeah, but when they are put together and allow their flavors to meld, magical things happen.

I hope you enjoyed reading this entry in the “National Foodball League” Project as much as I enjoyed researching and writing it. Stay tuned for more history/sports/culinary adventures in the weeks to come.

Mike returns to the “Foodball League Project” with an entry about the Steel City of Pittsburgh.